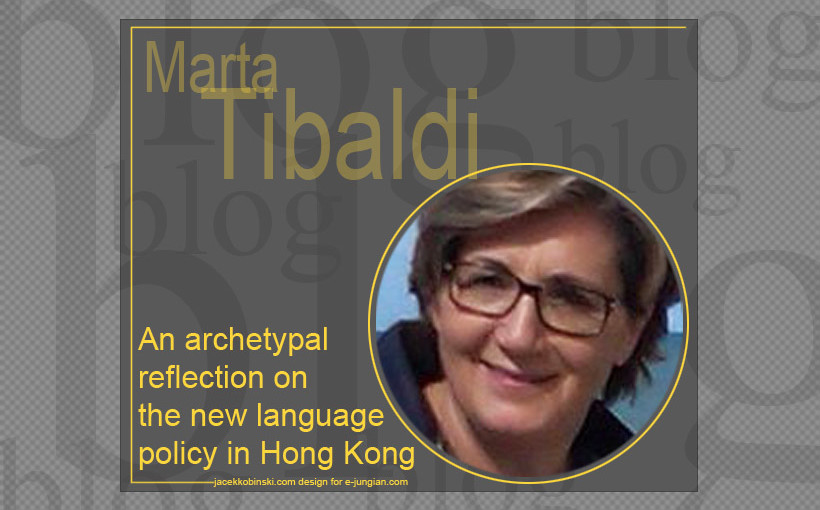

The article originally published at Marta Tibaldi’s blog

Republished thanks to the courtesy of the author

Discalimer:

This post doesn’t express any political opinion. All data and information provided are only for personal psychological purpose.

A Chinese proverb says that „when the wind of change blows, some build walls, some others windmills.” There is no doubt that since the handover in 1997, Hong Kong and its people are facing a wind of change that might build „emotional walls” between Hong Kong and China. The problem arises from the compulsory replacement of Cantonese – the Guang Dong province and Hong Kong people’s mother-tongue – by Putonghua – the official language in China – in schools. (The English name „Cantonese” comes from the fact that Guang Dong was the main trading port in the end of Quing dynasty. So the expats traderds called this place „Canton”, thus „Cantonese” as the spoken language.)

The Hong Kong government’s language policy is going straight in the direction of implementing Mandarin, advocating biliteracy and trilingualism: „The promotion of Mandarin is extensive, from school level via curriculum and public exams, to the public sphere such as radio, television and public utilities announcement. […] Authorities are now promoting Putonghua as the medium of instruction in Chinese language lessons (PMIC) in a low-profile manner, as there’s no research data backing up the advantages of using Mandarin over Cantonese in the instruction of Chinese language.”(„Why our young generation will stay on guard over language policy, Ejinsight, March 19, 2016.)”

Beyond the political reasons – the new language policy serves as the best starting point to construct national identity in the Hong Kong youth – the government’s decision to speed up the amalgamation of Hong Kong and mainland China thanks to the language policy is creating some worries in the Hong Kong parents. It is now difficult to find a school that uses Cantonese as the medium of instruction in Chinese language lessons: „Cantonese might soon be labeled as a dialect for family and regional usage only” and this is provoking a change in the identity of the Hong Kong people.

Beyond the political reasons – the new language policy serves as the best starting point to construct national identity in the Hong Kong youth – the government’s decision to speed up the amalgamation of Hong Kong and mainland China thanks to the language policy is creating some worries in the Hong Kong parents. It is now difficult to find a school that uses Cantonese as the medium of instruction in Chinese language lessons: „Cantonese might soon be labeled as a dialect for family and regional usage only” and this is provoking a change in the identity of the Hong Kong people.

Marshall Lee, a brillian young psychiatrist who is training as a Jungian analyst in Hong Kong, recently informed me about this language issue. He pointed out how the emotional experience of the new language policy is perceived as a weakening of their previous identity: „HK people in general are in identity crisis, both culturally and politically. In fact, we feel we are following steps of Tibet and Guangzhou, where the influx of mainland migrants and denigration of local language are going hand in hand.” He let me know the picture labeled on the top of this post: it is the slogan in a primary school in Guangzhou, saying „speaking Putonghua, and writing simplified Chinese, be a civilised person”.

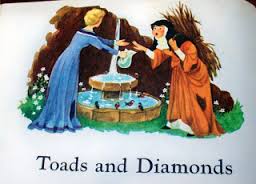

Leaving by side any political consideration, I would like to reflect on the change of identity that the Hong Kongers are facing since the handover in 1997 from an archetypal perspective, referring to the relational pattern between a „step-mother” and a „step-daughter” as highlighted in a Fairy Tale such as, for example, Perrault’s Diamonds and Toads.

Very briefly Perrault’s Fairy Tale tells the story of „an old widow” who had two daughters, Fanny and Rose: „Fanny was disagreable and proud but looked and behaved like her mother and therefore was her favorite child; Rose, the younger daughter, was sweet, compassionate and beautiful but resembled her late father. Jelous and bitter, the widow and her favorite daughter abused and mistreated the younger girl.” In the woods Rose met a Fairy in the shape of an old beggar, she was kind to her and the Fairy gave her the gift of having either a jewel, a precious metal or a pretty flower from her mouth whenever she spoke. Back home, the step-mother wanted Fanny to get the same gift and sent the elder daughter to meet the Fairy in the woods. This time the Fairy appeared as a princess and Fanny was very rude to her. As punishment for her bad behavior, Fanny got from the Fairy that either a toad or a snake would fall from her mouth whenever she spoke. Back home again the widow was in fury with Fanny and drove her younger daughter (sic) out of the house. In the woods Rose met a king’s son who fell in love with her and married her. In time the old widow was so sickened by Fanny that drove her out and died alone and miserable.

Although Perrault’s Diamonds and Toads might appear miles away from the problem of the new language policy in Hong Kong, symbolically speaking there are some elements in common: Rose as Hong Kong became „a step-daughter” after „the father’s death”, that is the handover in 1997. What about considering the beautiful Hong Kong, „the pearl of Orient”, „the fragrant Harbour” as a younger daughter who lost her father – the British government – facing a sudden change of her identity? No doubt that Hong Kong is a city of a vibrant beauty that willy-nilly exceeds in that all other cities. Can we approach the relationship between China and Hong Kong along the archetypal pattern of those between „a step-mother” and „a step-daughter that desn’t look and behave like her mother” – the Chinese style – and therefore cannot be appreciated by her in her diversity?

Going back to the Fairy Tale, we know that archetypal narrative are precious material that not only indicates the present situation („a change of identity”) and the problem („cannot be appreciated in her diversity”) but also show the resources we can draw and the possible solution of the story’s action. In Diamonds and Toads the resources come to the younger daughter from „the woods”, the world of the unconscious: Rose meets the Fairy and the king’s son in the depth of her psyche and finds there its creative aspects and the noblest form of her positive masculine principle. These deep resources will balance the destructive power of „a negative mother complex” represented by „the step-mother”.

Under this regard I want to quote once more what the young colleague Marshall Lee wrote me and whose thoughts seem to go in same direction: „Recently I am reading more on the history of Cantonese and some ghost stories written back in 300 AD. I was amazed to find myself able to understand the text more or less. When I read out aloud, some of the words still being used in exactly the same way in modern colloquial Cantonese! After starting on my personal and router journey [the Jungian training program] for some time, I have the sense that I have to go into deeper layer of tribal and cultural level in order to further my studies.”

C.G. Jung’s analytical psychology do not claim to give political answers but certainly can offer psychological reflections and archetypal understandings of winds of change and apparent impassable walls in front of us.