“To be well is a hobby;

to be sick is a full time job.”

One of the central experiences of illness is loss.

In English, the word for illness is dis-ease

The loss of ease—

the ease not to know

when your next treatment or blood test is coming.

The loss of ease that each sensation, pain, sweaty night,

each ache, does not signal another medical earthquake.

The loss of a future spreading out before you like a set table.

Above all, for every cancer person,

there is the loss of “my body as I knew it.”

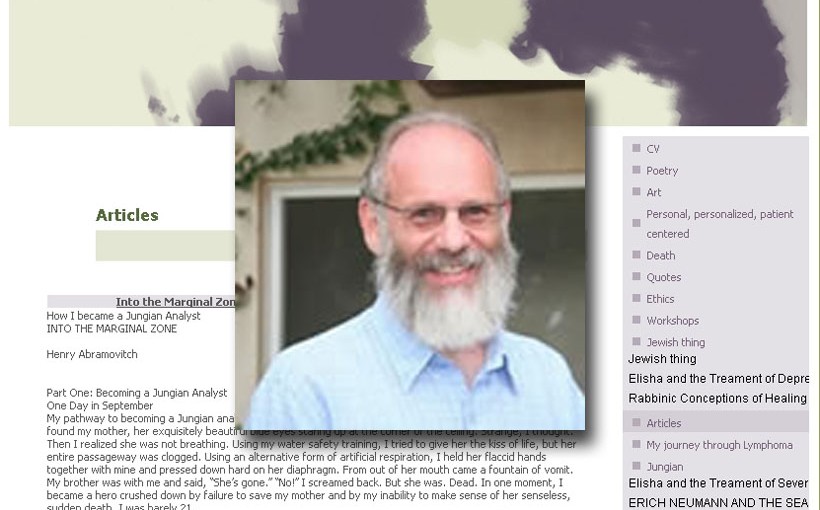

Henry Abramovitch

A beautiful article by Henry Abramovitch about his pathway to become an Jungian analyst. A must read for everyone thinking about the deep meaning of analyst’s woundedness in analytical practice. The article was published in Marked By Fire: Stories of the Jungian Way [The Fisher King Review Volume 1].

From the article:

How has this experience changed me? When I was going through treatments and confronting mortality, I yearned for a spiritual breakthrough that would refocus my life. But it never came. I did decide to explore my inferior sensation function by learning to play saxophone and doing yoga and ceramic sculpture. But there was no great revelation. Rather, I gradually returned to doing what I had done previously but with more zest. Following his slow recovery from his heart attack, Jung (1989) wrote:

„. . . something else, too, came to me from my illness. I might formulate it as an affirmation of things as they are: an unconditional “yes” to that which is, without subjective protests—acceptance of the conditions of existence as I see them and understand them, acceptance of my own nature, as I happen to be. (p. 328).”

In a less dramatic fashion, as I left the village of the sick, I believe that I too accepted my own nature. Jungian psychology, with its emphasis on spirit and Self, often neglects the body, and my illness has taught me to be more attentive and kind and appreciative of it. Nadezhda Mandelstamm, wife of the great Russian poet Osip, in her memorable memoir Hope Against Hope (1999), describes how her husband was exiled and persecuted unto death by Stalinists. Despite all that, she described him as “endlessly zhizneradostny”— literally, “life glad.” I believe my illness has shown me how to be zhizneradostny.

My illness had yet another impact. I became concerned with how illness and dying/death impact on the lives of analysts and their patients (Dewald, 1982; Kaplan & Rothberg,1986; Schwartz & Silver, 1990). In my training the issue of the ill or disabled analyst never arose, and I felt like I was making it up as I went along. I began investigating the topic and found little Jungian material, except a moving piece by Pamela Power about how the death of her analyst had impacted her life and her own illness (Power, 2005). I started interviewing analysts who were sick and those who had recovered, as well as patients of deceased analysts, while writing giving seminars,and workshops on the topic (Abramovitch, 2011). I now understand that it is crucial to confront our own illness and mortality before we get sick, otherwise the impact on the patients about whom we so care will be terrible. Ideally, patients of seriously ill or dying analysts ought to be transferred ahead of time (Kaplan & Rothberg, 1986). Yet, I know from personal experience with dying colleagues and their analysands how difficult it was for them to let go of their patients, who provided them with so much vitality and meaning. Analysands often complained bitterly that they had stayed in analysis only for the sake of their analyst, long after it ceased to be for their own needs. They also said how hard it was to start with someone else. The unexpected and unworked- through death of an analyst can have a profound and disturbing effect not only on analysands and candidates but on the entire analytical community (Lasky, 1990; Fajardo, 2001). I hope when my times comes to join my mother in the realm of the ancestors, I will have the courage to follow my own good advice.

I want to end with a poem by Osip Mandelstamm that brings together the themes of death, resurrection, and joy in living:

Mounds of human heads are wandering into the distance.

I dwindle among them. Nobody sees me. But in books

Much loved, and in children’s games I shall rise

From the dead to say the sun is shining.

Henry Abramovitch

Henry Abramovitch is a Jungian analyst, clinical psychologist, anthropologist and medical educator. He is the founding President of Israel Institute of Jungian Psychotlogy, Past President of the Israel Anthropological Association, as well as Professor in Dept of Medical Education, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, where he has been Director of Behavioral Science in New York/American Program for over 30 years.

His forthcoming books include:

- Brothers and Sisters: Myth and Reality will be published by Texas A & M University Press 2014.

- When Arjuna Refused To Fight & Other Puzzling Moments in the Life of Jesus, Buddha, Socrates, Abraham, Moses and Odysseus

- The Performance of Analysis: Clinical & Jewish Perspectives will be published in Russian

He conducts dream groups, workshops on professional ethics, siblings and does supervision for training candidates („routers”) in Russia and Poland. He is active in Interfaith Encounter Association.

Tags: analysts, Henry Abramovitch, illness, individuation, wounded healer

[…] “To be well is a hobby; to be sick is a full time job.” One of the central experiences of illness is loss. In English, the word for illness is dis-ease The loss of ease— the ease not to know when your next treatment or blood test is coming. […]

[…] Four: Dark Night of the Body Karlyn M. – Ward Voices Henry Abramovitch – Into the Marginal Zone Sharon Heath – The Church of Her […]